Ending Fuel Poverty

Fuel poverty is a political choice. It’s time to put people before profit to deliver affordable, clean energy for all for life’s essentials.

Energy For All

Read about our plan to provide everyone with enough energy to cover life's essentials

Prepayment Meters

No one should be cut off from the energy they need to stay healthy

No one should have to live in fuel poverty

Everyone should have enough energy to cover the basics

In twenty-first century Britain, most of us expect to have light and power at the switch of a button, and to be able to cook and heat our homes without having to go out every day to search for fuel.

We are privileged to live in a place and time where this is the case.

Yet every day, Fuel Poverty Action hears from people who cannot meet their basic energy needs.

We don’t see why the system should remain so unfair and destructive.

That’s why we are campaigning for energy justice on many levels. We propose solutions to the waste, pollution, misery, and injustice built into how energy is supplied.

- Every year thousands of people get sick or die because they can’t keep warm

- Millions of households are in debt due to unaffordable energy bills

- People are still having their homes broken into by energy companies to install prepayment meters without consent

- Energy bills in electric-only homes are up to four times more expensive than for those on the gas grid – despite the fact that renewable electricity costs four times LESS than gas to produce

- We are charged a higher price per unit of electricity the less we use, penalising those who are low users for economic or environmental reasons.

- Tariffs for charging electric cars are cheaper than tariffs for low-income people who want to charge a storage heater overnight

- Many people living with (often faulty) district heating networks can have huge bills built into their rent over which they have no control

- Private companies are profiteering at every stage of the energy system, from generation through distribution to supply

- The energy regulator, Ofgem, protects the interests of private companies, not consumers

- Decades since we understood about climate change, and had the technology to decarbonise electricity, we are still reliant on burning dirty, polluting, expensive fossil fuels

- UK housing is some of the worst in Northern Europe, the schemes to upgrade it have been mismanaged and slow, and homes are still being built that are not energy efficient

- Global firms are being invited RIGHT NOW to buy up our renewable energy infrastructure, guaranteeing high energy bills for years to come

- The Government is investing billions of pounds in expensive false solutions like nuclear power, hydrogen and carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS)

News and updates

Read article: October 1st: Labour Conference Protest!

Read article: October 1st: Labour Conference Protest!

October 1st: Labour Conference Protest!

Join us to demand Energy For All NOW. On October 1st, energy bills are predicted to rise again… the same day the Labour Party concludes its conference in Liverpool.

Read article: Retrofit for the Future campaign launches

Read article: Retrofit for the Future campaign launches

Retrofit for the Future campaign launches

There’s no time to lose to fight fuel poverty and climate disaster.

That’s why we’ve teamed up with the Peace and Justice Project, ACORN, Greener Jobs Alliance and CACC to campaign for three key interventions in the retrofit debate: accountability for retrofit work, protecting renters and skilling up our workforce.

Read article: Unions counter far-right climate lies

Read article: Unions counter far-right climate lies

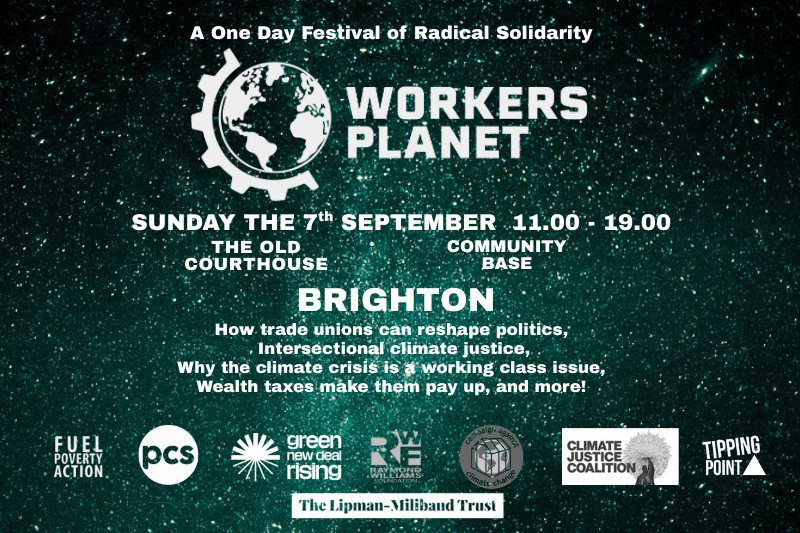

Unions counter far-right climate lies

Trade unionists and climate campaigners issue urgent call to tackle climate misinformation and the far right